All work, no play – and a bit of learning

Childhood, as a separate and significant phase of life, was not always distinct from adulthood – until the last few hundred years, children dressed the same as adults and participated in activities as an adult might, particularly as part of the familial economic unit. However, as Britain industrialised, education and child welfare became more of a social priority, which led to a number of law changes…

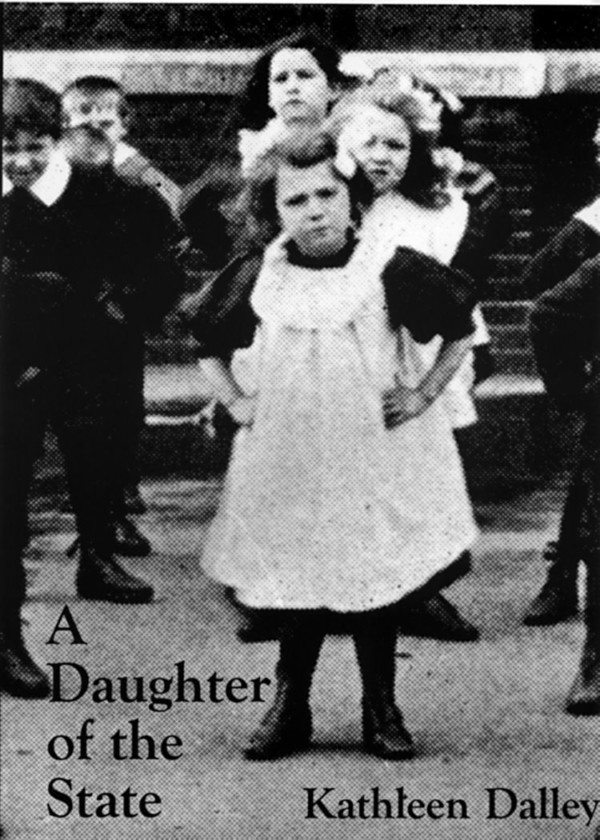

By 1878, the employment of children under the age of 10 in factories was banned, and this paved the way for an Education Act two years later, making schooling compulsory until the age of 10. Over the next 30 years, further acts and a charter allowed the state to intervene in family relationships if a child was believed to be at risk. The first register for foster parents was created, coinciding with the establishment of the NSPCC. Within the first decade of the twentieth century, another Children’s Act had also established juvenile courts so that children could no longer be treated as adults in the eyes of the law. As the century progressed, further acts continued to place child welfare at the heart of local authority social services, and to raise the compulsory school-leaving age.

Nevertheless, throughout the 1900s childhood could still be hard work, as numerous tales in QueenSpark’s books testify:-

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 saw fathers leaving their homes to fight, plunging many of their families into poverty and uncertainty. Lillie Morgan’s family moved from Ilford to Brighton after the Zeppelin air raids began, in search of safety. For Lillie’s 12 year old sister, the move meant the end of her education; Lillie herself began working at a Brighton pawnbrokers at the age of 15. Her days were long, from 7.30am until well into the night – as she relates in At the Pawnbrokers…

The War really hit the women hardest, especially those with young children. With their husbands away in the forces they only received a small pittance as an allowance, which was not enough to live on. Sometimes there simply was not enough money even to buy their children breakfast before they went to school, so they pawned their sheets and blankets (you could get 9d for a decent sheet), probably owning nothing of higher value, and then they would cross the road to the bakers and buy buns for their children. I remember plenty of barefoot children in those days and we were told never to take children’s shoes into pawn, but then these sorts of people probably couldn’t have afforded to buy their children shoes in the first place.

Some work, some play – and a bit of punishment…

In George Parker’s memoir The Tale of a Boy Soldier, he recounts his experiences of corporal punishment in a Brighton school. Whilst the state had had the power to intervene between parent and child for three decades, it did not, it seem, apply to other adults in contact with children:

In school at that time, tanning was a regular thing. After a serious offence, a few of the masters were in the habit of making a boy lay across the master’s desk, and then they really laid it on.

However, after these kinds of punishments for school misdemeanours, the state was more than happy to collude in a child’s rule-breaking when it suited:

Mind you, I had no idea what I was letting myself in for. Inside the office there was a Recruiting Sergeant and an Officer, as well as a Medical Officer. I was really scared, but the Sergeant asked me what I wanted, I looked so young. Then I said that I wanted to join up, and he looked at me as if I should still be in my cradle. I suppose he was not far wrong! He asked my age and I boldly said “18 years.” He looked at me with a smile, and asked “Does your mother know that you are 18?” Then he said “All right, son,18 it is.” He took my name, and passed me over to the MO who had me strip naked, examined and passed me. The Officer then made me take the Oath of Allegiance and there I was, a soldier at 15 3/4.

In The Town Beehive, Daisy Noakes remembers a busy childhood as one of ten children pitching in, in the 1910s. The family’s week was organised around the various household chores that dominated her mother’s life and must have prepared her well for when she entered domestic service in Brighton herself at the age of 14:

The first child down in the morning would slice and cut bread in squares to be shared among five or six basins, depending on how many were attending school. By this time the brother who had been out with Dad would return, and depending on how much milk was in our can, we would have milk over our bread or cocoa. This was our breakfast every day.

Following the war, construction of the Moulsecoomb estate began, initially to welcome back the war heroes. In Moulsecoomb Days, Ruby Dunn members her childhood there fondly:

My family loved it there, in the heart of the countryside. It was not long before I was old enough to enjoy the delights of playing on the wide green facing our house, or walking with my big sisters up to the head of the valley, to pick the wild scabious and poppies, or to play hide-and-seek among the corn stooks.

Before war broke out again in 1939, life for children – up to the age of 14 anyway – was organised around the school day. But between 1940 and 1944 Brighton was repeatedly attacked and children often stayed at home, missing school; when the sirens sounded, education was interrupted and children were expected to walk in an orderly fashion into the air raid shelter on the playground. For some, it was a welcome distraction:

Air raid drills were always enjoyed. Once gathered underground in the shelters built under the playground, we were given a barley sugar each to last until the ‘all clear’. Gordon Mills, School Reports.

As Britain fought, its government was looking ahead to post-war reconstruction, with more house-building initiatives and improvements to education. After the war, the school leaving-age rose to 15, and the state assumed responsibility for education rather than the local authority. More funding was made available, fee-paying at state schools was prohibited and a national programme of building the purpose-built secondary modern schools began.

All play, no work…

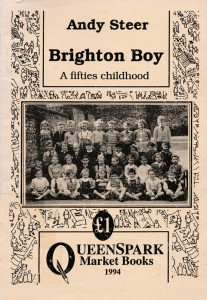

Decades on from the original factory and education acts, by the 1950s many children were having childhoods very different from earlier generations – Andy Steer, in A Brighton Boy, illustrates how childhood had, for many, moved from work to play:

School I remember mostly for the games – the inevitable football in winter and cricket in summer but other things cropped up like hand-tennis, where the technique to cultivate seemed to be a chop of the hand to produce the slice serve. It cost nothing and my brother Al and I got so keen on it that we chalked out courts on the carpark at Withdean Stadium to get in extra practice.

Then as now, prowess in any game equalled status among school children. Doing well in class was frowned on so the expert marble player, crack hand-tennis player or cigarette-card flicker would all have their periodic glory. Such games, I recall, were just crazes that gripped the childish mind suddenly. At the time they absorbed us totally and, when the obsession cooled, were dropped just as suddenly because something else had come along – paper darts, cotton-reel-and-candle tank battles, water-bombs – the list was endless.

Many QueenSpark books feature stories of education – you can read them for free on our archive, or browse a selection of free downloadable pdfs in our bookshop.